The History of Acadia National Park and

Mount Desert Island

The striking scenery and diverse resources of Mount Desert Island have attracted people for thousands of years. The first inhabitants, Native Americans here more than 5,000 years ago, were followed by the French and English. By the 1800s, settlers were arriving in large numbers and engaging in fishing, shipbuilding, farming, and lumbering. The island became known to the world in the late 1800s, when artists depicted its beauty in paintings. The rush to experience Mount Desert Island, and the desire to protect its lands, had begun.

Early History

Deep shell heaps indicate Native American encampments dating back 5,000 years in Acadia National Park, but pre-European records are scarce. The first written descriptions of Maine coast Indians, recorded 100 years after European trade contacts began, describe Native Americans who lived off the land by hunting, fishing, collecting shellfish, and gathering plants and berries.

The Wabanaki people knew Mount Desert Island as Pemetic, “the sloping land.” They built bark-covered conical shelters and traveled in birchbark canoes.

Historical records indicate that the Wabanaki wintered in interior forests and spent summers near the coast. Archeological evidence, however, suggests the opposite pattern: to avoid harsh inland winters and take advantage of salmon runs upstream, Native Americans wintered on the coast and summered inland. There may even have been two separate groups, one inland and another on the coast.

Path Committee at Jordan Pond, Sept 1923

New France

The first meeting between the people of Pemetic and the Europeans is unknown, but a Frenchman, Samuel Champlain, made the first important contribution to the historical record of Mount Desert Island. He led the expedition that landed on Mount Desert on September 5, 1604, and wrote in his journal, “The mountain summits are all bare and rocky... I name it Isles des Monts Déserts.” Champlain’s visit to the island 16 years before the Pilgrims landed at Plymouth Rock destined this land to become known as New France before it became New England.

In 1613, French Jesuits, welcomed by native people, established the first French mission in America on Mount Desert Island. They had just begun to build a fort, plant corn, and baptize the natives when an English ship commanded by Captain Samuel Argall destroyed their mission.

The English victory doomed Jesuit ambitions on Mount Desert Island, leaving the land in a state of limbo lying between the French, firmly entrenched to the north, and the British, whose settlements in Massachusetts and southward were becoming increasingly numerous. No one wished to settle in this contested territory. For the next 150 years, the island’s importance was primarily its use as a landmark for seamen.

There was a brief period when it seemed Mount Desert would again become a center of French activity. In 1688, Antoine Laumet, an ambitious young man who had immigrated to New France and bestowed upon himself the title Sieur de la Mothe Cadillac, asked for and received a hundred thousand acres of land along the Maine coast, including all of Mount Desert Island. Cadillac’s hopes of establishing a feudal estate in the New World, however, were short lived. Although he and his bride resided here for a time, they soon abandoned their enterprise. Cadillac later gained lasting recognition as the founder of Detroit.

New England

In 1759, after a century and a half of conflict, British troops triumphed at Quebec, ending French dominion in Acadia. With Native Americans scattered and the fleur-de-lis banished, lands along the Maine coast opened for English settlement. Governor Francis Bernard of Massachusetts obtained a royal land grant on Mount Desert Island. In 1760, Bernard attempted to secure his claim by offering free land to settlers. Abraham Somes and James Richardson accepted the offer and settled their families at what is now Somesville.

The onset of the Revolutionary War ended Bernard’s plans for Mount Desert Island. In the aftermath of the war, Bernard lost his claim, and the newly created United States of America granted the western half of Mount Desert Island to John Bernard, son of the governor, and the eastern half of the island to Marie Therese de Gregoire, granddaughter of Cadillac. Bernard and de Gregoire soon sold their landholdings to nonresident landlords.

Their real estate transactions probably made very little difference to the increasing number of settlers homesteading on Mount Desert Island. By 1820, farming and lumbering vied with fishing and shipbuilding as the major occupations. Settlers converted hundreds of acres of trees into wood products ranging from schooners and barns to baby cribs and hand tools. Farmers harvested wheat, rye, corn, and potatoes. By 1850, the familiar sights of fishermen and sailors, fish racks and shipyards, revealed a way of life linked to the sea.

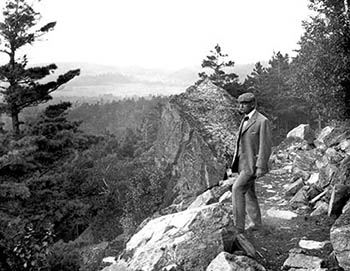

George B. Dorr on the Beachcroft Path, on Huguenot Head

Rusticators and Cottagers

It was the outsiders—artists and journalists— who revealed and popularized this island to the world in the mid-1800s. Painters of the Hudson River School, including Thomas Cole and Frederic Church, glorified Mount Desert Island with their brushstrokes, inspiring patrons and friends to flock here. These were the “rusticators.” Undaunted by crude accommodations and simple food, they sought out local fishermen and farmers to put them up for a modest fee. Summer after summer, the rusticators returned to renew friendships with local islanders and, most of all, to savor the fresh salt air, beautiful scenery, and relaxed pace. Soon the villagers’ cottages and fishermen’s huts filled to overflowing, and by 1880, 30 hotels competed for vacationers’ dollars. Tourism was becoming the major industry.

For a select handful of Americans, the 1880s and the “Gay Nineties” meant affluence on a scale without precedent. Mount Desert, still remote from the cities of the east, became a retreat for prominent people of the times. The Rockefellers, Morgans, Fords, Vanderbilts, Carnegies, and Astors chose to spend their summers here. Not content with the simple lodgings then available, these families transformed the landscape of Mount Desert Island with elegant estates, euphemistically called “cottages.” Luxury, refinement, and large gatherings replaced the buckboard rides, picnics, and day-long hikes of an earlier era. For more than 40 years, the wealthy held sway on Mount Desert, but the Great Depression and World War II marked the end of such extravagance. The final blow came in 1947 when a fire of monumental proportions consumed many of the great estates.

Sieur de Monts Spring

Preserving Acadia National Park

Though they came to the island in search of social and recreational activities, the affluent of the turn of the century had much to do with preserving the landscape we know today. George B. Dorr, a tireless spokesman for conservation, came from this social strata. He devoted 43 years of his life, energy, and family fortune to preserving the Acadian landscape.

In 1901, disturbed by the growing development of the Bar Harbor area and the dangers he foresaw in the newly invented gasoline-powered portable sawmill, Dorr and others established the Hancock County Trustees of Public Reservations. The corporation, whose sole purpose was to preserve land for the perpetual use of the public, acquired 6,000 acres by 1913. Dorr offered the land to the federal government, and in 1916 President Wilson announced the creation of Sieur de Monts National Monument. Dorr continued to acquire property and renewed his efforts to obtain full national park status for his beloved preserve. In 1919, President Wilson signed the act establishing Lafayette National Park, the first national park east of the Mississippi. Dorr, whose labors constituted “the greatest of one-man shows in the history of land conservation,” became the first park superintendent. In 1929, the name changed to Acadia National Park.

Today the park protects more than 47,000 acres, and the simple pleasures of “ocean, forests, lakes, and mountains” that have been sought and found by millions for over a century and a quarter are yours to enjoy.

—article courtesy National Park ServiceVisit www.nps.gov/acad for more information.